On low-rung politics (aka Political Disney World)

This post is part of a series on Tim Urban’s book, What’s Our Problem? a self-help book for societies.

--

Last week we discussed high-rung politics, based on a culture of intellectual humility and open, nuanced debate. Today, we'll explore low-rung politics, or what Tim Urban fittingly calls Political Disney World.

The idea is simple: the Disney movies we all love feature characters that are either purely good or purely evil. There are no shades of gray. This black-and-white portrayal makes sense given that Disney films are made for kids. But oversimplifying real life in a similar way can be dangerous. Tim argues that low-rung, polarized politics has come to resemble a Disney movie, with virtuous or villainous characters, right or wrong policies, and positive or devastating election results.

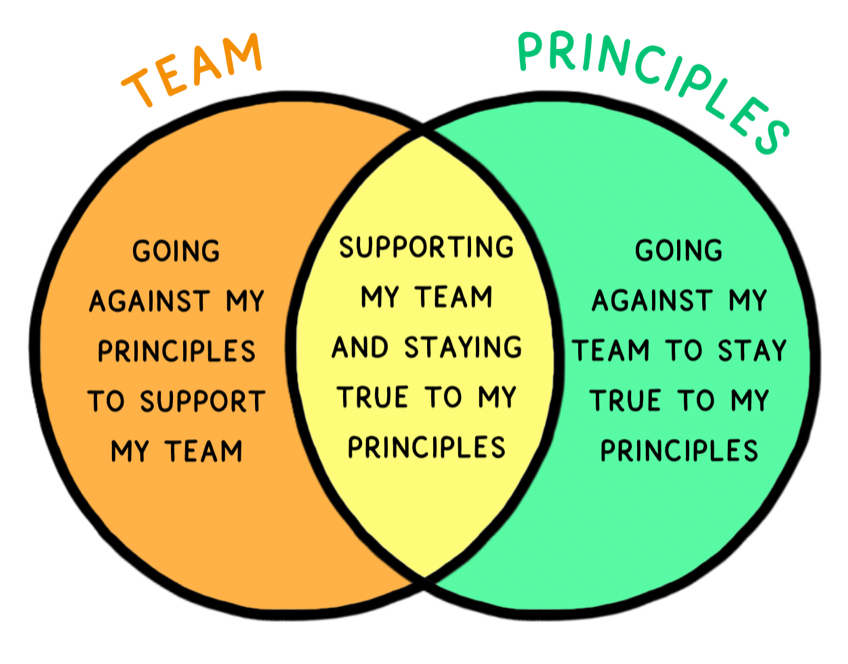

Political Disney World is characterized by conformity within the tribe and an attachment to a particular worldview and narrative. When the group’s narrative clashes with personal principles, there’s a strong urge to accept the group perspective, especially if personal principles are weak.

The tribe also employs a number of effective tactics to keep individuals in line.

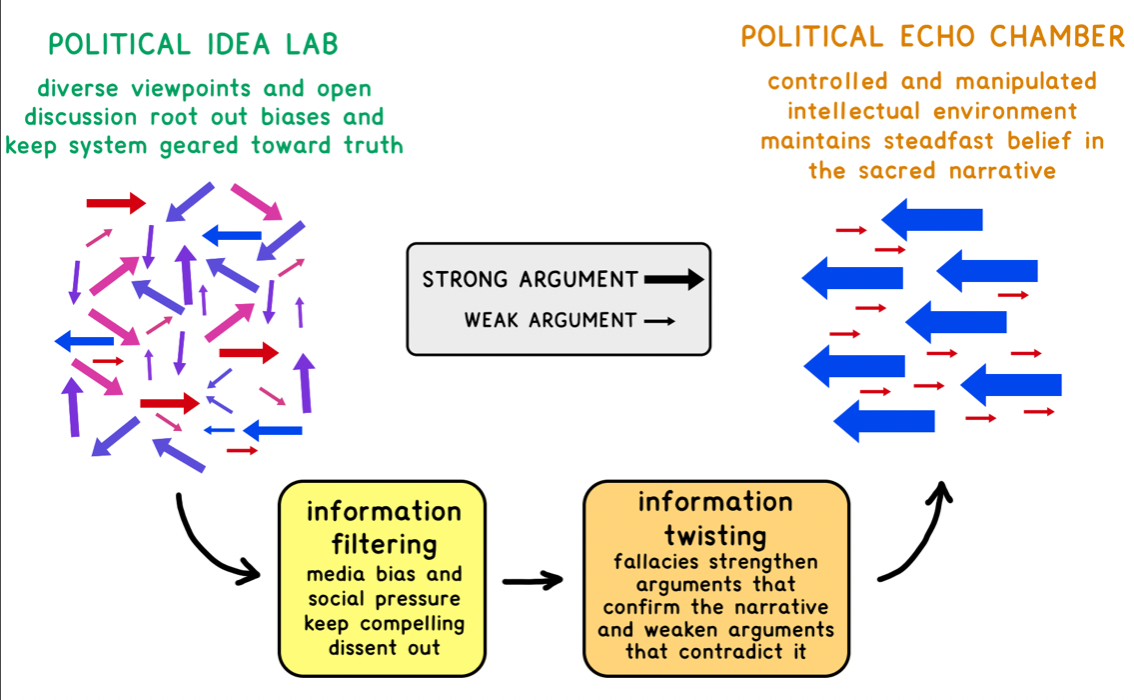

Information filtering

Media sources that promote stories aligned with the tribe’s narrative are promoted, while those that challenge the narrative are downplayed or outright ignored, regardless of veracity. Inconvenient truths are unacceptable. The echo chamber nature of the tribe has a chilling effect that discourages dissenting opinions from emerging.

Information twisting

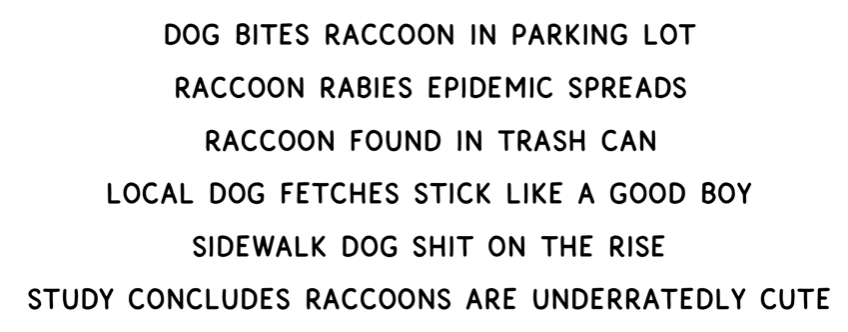

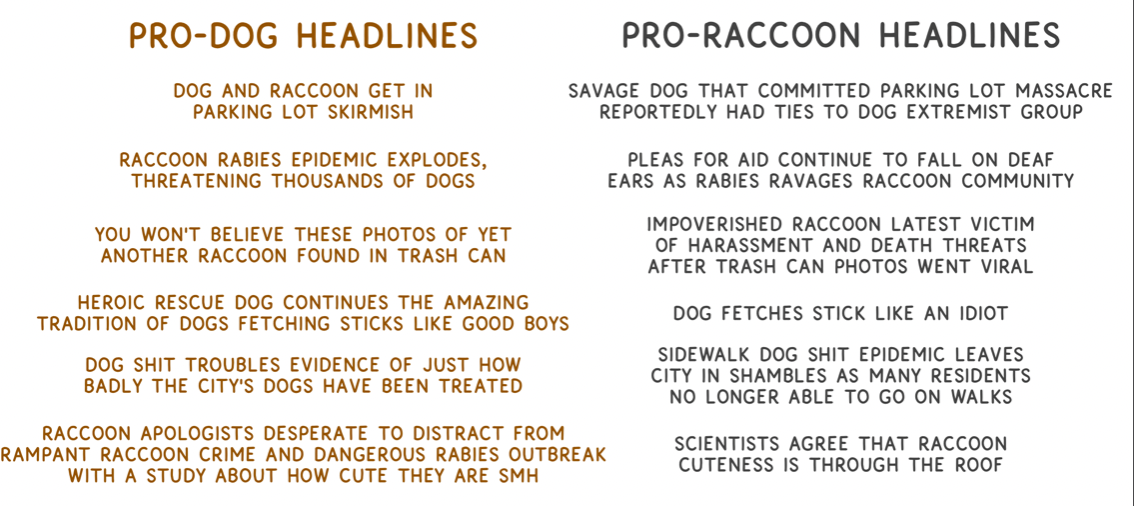

Participants in low-rung politics use logical fallacies, whether by accident or design, to great effect. These include swapping trends and anecdotes, confusing correlation and causation, constructing a weak version of the opposing argument, or dismissing an argument based solely on who makes it. Here’s a hilarious yet illustrative example of how stories can be twisted and shaped to suit a particular narrative:

Confirmation bias

When information filtering and distortion work well, they create the ideal conditions for confirmation bias to thrive. Members of a political tribe rarely encounter opposing views, and when they do, they usually see the weakest versions of those positions. Repeated exposure to this reinforces the narrative, as social pressure to agree with the group acts as confirmation.

In healthy societies, political idea labs and echo chambers operate at an acceptable balance. But equilibrium is not permanent. In the next post in this series, we’ll examine how things have gotten out of balance in recent years.